Founding Father Quote of the Week

A wise and free people must focus their attention on many objectives. First is safety. The concept of safety relates to a wide variety of circumstances and ideas, giving latitude to people who wish to define it precisely and totally. ~ John Jay

Founding Father Quote of the Day

One of the most essential branches of English liberty is the freedom of one’s house. A man’s house is his castle. ~ James Otis

The Civil War, Part 3; Abraham Lincoln

![]()

The following is the last of a three part series on the Civil War; and while the Civil War is a complicated and controversial topic, I feel the misinformation that is currently out there must be addressed. In the first installment we covered the reason the South seceded from the Union; in the second chapter we dealt with which side started the war; and in this final installment we address President Lincoln.

*Note to the Reader*: There will be quotes in here from Lincoln that may make you want to stop reading, as you may feel you can form your opinion on them; but I encourage you to not stop reading halfway, but to instead read all the way through if you want to get a more complete understanding of our 16th president.

______________________________________________________________

When it comes to Abraham Lincoln, it seems everyone has an opinion; people in the North generally view “Honest Abe” as an American hero, a man who did indispensible good for the nation in helping to end slavery. People in the South on the other hand generally speak of Lincoln with disdain on their lips, believing him to be a deplorable tyrant and a despicable man. But no matter what our preconceived biases are, we must make sure to avoid two very common traps when judging history.

The first trap we must avoid in our study is painting Lincoln, or any historical figure for that matter, with a broad brush. The second being that we must avoid viewing historical figures through the rose colored glasses of our society and beliefs; if we truly want to understand figures from history, understand what they believed and why, we must put ourselves in their shoes. It is the least we can do, and we must hope that people 150 years from now afford us the same courtesy. So who was Lincoln? Let’s find out:

Lincoln and Slavery

One of the interesting, and frankly frustrating criticisms of President Lincoln is that he really did not care about slavery, and had no real interest in seeing the institution ended; these claims are usually based on quotes that are misunderstood and taken out of the context that Lincoln was speaking in. If detractors were to read Lincoln’s full comments on slavery however, they would come to a much different conclusion; a conclusion that states that Abraham Lincoln was indeed anti-slavery.

Going back to before he was President, Abraham Lincoln expressed a real hatred for the institution and the very idea of slavery; take for example Lincoln’s speech at Peoria, Illinois in 1854, where he said:

“Slavery is founded in the selfishness of man’s nature – opposition to it, is his love of justice. These principles are an eternal antagonism; and when brought into collision so fiercely, as slavery extension brings them, shocks, and throes, and convulsions must ceaselessly follow.” (1)

In that same speech, Lincoln would say:

“I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world.” (2)

Lincoln shows that he hates slavery not only because it is based in selfishness, antagonism, and injustice, but also because it goes against the very principles of our Republic; but Lincoln wasn’t finished with the issue of slavery in that speech, as he also proclaimed:

“What I do say is, that no man is good enough to govern another man, without that other’s consent. I say this is the leading principle – the sheet anchor of American republicanism.” (3)

Lincoln says that governance over another without consent (which is what slavery is) is completely contrary to the very anchor of the American republic, because no man is good enough to do so; a few days earlier in Springfield, Lincoln had this to say about slavery:

“We were proclaiming ourselves political hypocrites before the world, by thus fostering Human Slavery and proclaiming ourselves, at the same time, the sole friends of Human Freedom.” (4)

With similar reasoning, Lincoln spoke of the selfishness and hypocrisy of slavery on yet another occasion:

“So plain that no one, high or low, ever does mistake it, except in a plainly selfish way; for although volume upon volume is written to prove slavery a very good thing, we never hear of the man who wishes to take the good of it, by being a slave himself.” (5)

In the same speech, Lincoln warned those who were pro slavery about using skin color and intelligence as justifications for slavery; telling the pro-slavery crowd that the same rational logically could be used against them:

“If A. can prove, however conclusively, that he may, of right, enslave B.—why may not B. snatch the same argument, and prove equally, that he may enslave A?—You say A. is white, and B. is black. It is color, then; the lighter, having the right to enslave the darker? Take care. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with a fairer skin than your own. You do not mean color exactly? You mean the whites are intellectually the superiors of the blacks, and, therefore have the right to enslave them? Take care again. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with an intellect superior to your own. But, say you, it is a question of interest; and, if you can make it your interest; you have the right to enslave another. Very well. And if he can make it his interest, he has the right to enslave you.” (5)

Just under a year later, Lincoln further proclaimed his feelings about slavery, and how the very sight/idea of it causes him torment:

“In 1841 you and I had together a tedious low-water trip, on a Steam Boat from Louisville to St. Louis. You may remember, as I well do, that from Louisville to the mouth of the Ohio there were, on board, ten or a dozen slaves, shackled together with irons. That sight was a continual torment to me; and I see something like it every time I touch the Ohio, or any other slave-border.” (6)

Lincoln would have much more to say about the issue of slavery in the years 1858-59, further proving the disdain he had for the institution. In a letter to Henry L. Pierce and Others in April of 1858, Lincoln wrote:

“Those who deny freedom to others, deserve it not for themselves; and, under a just God, can not long retain it.” (7)

Furthermore, speaking in Chicago on July 10th of that year, Lincoln again made his position abundantly clear:

“I have always hated slavery, I think as much as any abolitionist.” (8)

One week later, Lincoln reiterated his wish not only to see the spread of slavery stopped, but also the practice itself exterminated:

“I did say, at Chicago, in my speech there, that I do wish to see the spread of slavery arrested and to see it placed where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in course of ultimate extinction.” (9)

In July and August of 1858, Lincoln spoke again of slavery:

“If we cannot give freedom to every creature, let us do nothing that will impose slavery upon any other creature.” (10)

…

“As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy.” (11)

But while Lincoln was himself very anti-slavery, he did foresee constitutional (legal) problems with the federal government trying to eliminate slavery; for example, in the Lincoln-Douglas debate at Galesburg, Lincoln stated:

“Now, I confess myself as belonging to that class in the country who contemplate slavery as a moral, social and political evil, having due regard for its actual existence amongst us and the difficulties of getting rid of it in any satisfactory way, and to all the constitutional obligations which have been thrown about it; but, nevertheless, desire a policy that looks to the prevention of it as a wrong, and looks hopefully to the time when as a wrong it may come to an end.” (12)

A few days following this pronouncement, Lincoln again spoke of the legal problems that were in the way of slavery’s abolition:

“I believe the declaration that ‘all men are created equal’ is the great fundamental principle upon which our free institutions rest; that negro slavery is violative of that principle; but that, by our frame of government, that principle has not been made one of legal obligation; that by our frame of government, the States which have slavery are to retain it, or surrender it at their own pleasure; and that all others—individuals, free-states and national government—are constitutionally bound to leave them alone about it. I believe our government was thus framed because of the necessity springing from the actual presence of slavery, when it was framed. That such necessity does not exist in the teritories[sic], where slavery is not present.” (13)

But despite his belief that ending slavery was blocked by the issue of legality, Lincoln still believed that slavery must eventually be ended, and that “a house divided” could not stand:

“In the first place, I insist that our fathers did not make this nation half slave and half free, or part slave and part free. I insist that they found the institution of slavery existing here. They did not make it so, but they left it so because they knew of no way to get rid of it at that time.” (14)

…

“A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently half-slave and half-free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved – I do not expect the house to fall – but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other.” (15)

As mentioned before, soon to be President Lincoln continued espousing these positions when addressing friends and voters alike; speaking in Cincinnati, Lincoln again spoke of slavery as being “morally wrong”:

“I think slavery is wrong, morally, and politically. I desire that it should be no further spread in these United States, and I should not object if it should gradually terminate in the whole Union.” (16)

Lincoln continued to make denouncements of slavery as 1859 continued, and they did not stop once he became President of the United States (17, 18, 19, 20). In 1860, Lincoln for a third time referred to slavery as being wrong on a moral level, while also stating that he still did not believe that he as President had a right to exterminate it in the slave-holding states:

“We think slavery a great moral wrong, and while we do not claim the right to touch it where it exists, we wish to treat it as a wrong in the territories, where our votes will reach it.” (21)

Two years later, Lincoln would describe what it means to give freedom to those bound in unjust slavery:

“In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free – honorable alike in what we give, and what we preserve. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth. Other means may succeed; this could not fail. The way is plain, peaceful, generous, just – a way which, if followed, the world will forever applaud, and God must forever bless.” (22)

Come 1864, Lincoln again offered his personal views on slavery as well as a defense of the then announced Emancipation Proclamation:

“I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel.” (23)

…

“I repeat the declaration made a year ago, that ‘while I remain in my present position I shall not attempt to retract or modify the emancipation proclamation, nor shall I return to slavery any person who is free by the terms of that proclamation, or by any of the Acts of Congress.’ If the people should, by whatever mode or means, make it an Executive duty to re-enslave such persons, another, and not I, must be their instrument to perform it.” (24)

When Lincoln’s life was coming to an end in 1865 (although he did not know it), the President gave one of his final denouncements against slavery, proclaiming what he thought should be done to any man who enslaves another:

“I have always thought that all men should be free; but if any should be slaves it should be first those who desire it for themselves, and secondly those who desire it for others… Whenever I hear any one arguing for slavery I feel a strong impulse to see it tried on him personally.” (25)

It is abundantly clear that Lincoln was, himself, very anti-slavery; so what of the quotes where he admits he would end the civil war by freeing none of the slaves if he could? The answer to this question, as mentioned in part one of this Civil War trilogy, is simply that Lincoln saw that his main duty and responsibility was to keep the Union together at all costs; detractors of Lincoln often fail to mention that in the same quote they like to tout, Lincoln also says he would free all the slaves if he thought it would keep the union together. As Lincoln himself said:

“What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union. I shall do less whenever I shall believe what I am doing hurts the cause, and I shall do more whenever I shall believe doing more will help the cause.” (26)

Lincoln and Race

Along with those who wrongly attack Lincoln on slavery, there are some who take highly questionable quotes from our 16th President and use them to paint him as a horrible monster who hated the African race at its core. Here are a few examples of the quotes they use:

“If all earthly power were given me…I should not know what to do, as to the existing institution [of slavery]. My first impulse would be to free all the slaves, and send them to Liberia, to their own native land… politically and socially our equals?…My own feelings will not admit of this…and [even] if mine would, we well know that those of the great mass of white people will not … We can not, then, make them equals.” (27)

…

“There is a natural disgust in the minds of nearly all white people to the idea of indiscriminate amalgamation of the white and black races … A separation of the races is the only perfect preventive of amalgamation, but as an immediate separation is impossible, the next best thing is to keep them apart where they are not already together. If white and black people never get together in Kansas, they will never mix blood in Kansas.” (28)

…

“I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and black races. There is physical difference between the two which, in my judgment, will probably forever forbid their living together upon the footing of perfect equality, and inasmuch as it becomes a necessity that there must be a difference, I, as well as Judge Douglas, am in favor of the race to which I belong having the superior position.” (29)

…

“I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races, that I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.” (30)

…

“You and we are different races. We have between us a broader difference than exists between almost any other two races. Whether it is right or wrong I need not discuss, but this physical difference is a great disadvantage to us both, as I think your race suffers very greatly, many of them, by living among us, while ours suffers from your presence. In a word, we suffer on each side. If this is admitted, it affords a reason at least why we should be separated.” (31)

…

“But what shall we do with the negroes after they are free?…I can hardly believe that the South and North can live in peace, unless we can get rid of the negroes…I believe that it would be better to export them all to some fertile country with a good climate, which they could have to themselves…If these black soldiers of ours go back to the South, I am afraid that they will be but little better off with their masters than they were before, and yet they will be free men. I fear a race war, and it will be at least a guerilla war because we have taught these men how to fight…There are plenty of men in the North who will furnish the negroes with arms if there is any oppression of them by their late masters.” (32)

So the crux of the argument against Lincoln is that he is despicable because he was a White supremacist who did not believe in racial equality and thought that the Negro race should be exported back to Africa; but it is here we must make sure not to fall into the two traps mentioned at the beginning of this piece. We must remember not to paint Lincoln with a broad brush, and to put ourselves in his shoes if we want to understand him; especially considering that Lincoln was a very complicated man.

It is obviously true that Lincoln did say these things, but we must remember that Abe was a man of his time; he had grown up in, was taught by, and made observations in a society where most people believed such things; and like it or not, if we were put in his same situation, the vast majority of us would most likely believe the same things he did. Does that make what he believed right? Absolutely not; but just because he was wrong in what he believed, does not mean he was a vile racist who hated the African race.

Putting aside the whole “man of his time” argument however, why exactly was Lincoln opposed to equality between the races? Simply put, it is because he did not think racial equality was feasible. As Lincoln himself said, there was a “natural disgust in the minds of nearly all white people” and that “the great mass of white people will not” approve of the equality (and amalgamation) of the races; to attempt such a thing would be rejected by the masses. Along with this, Lincoln, like most people, believed that there were “physical difference between the two which, in my judgment, will probably forever forbid their living together upon the footing of perfect equality” that is to say “social and political equality”; and that the differences caused disadvantages and suffering among both races.

The ironic thing about Lincoln’s point of view is that while it was wrong, it actually wasn’t fully wrong, at least not in the Southern parts of the United States; because for nearly 100 years after Lincoln died (1865-1964), Blacks and Whites in the South did not get along, were not equal, and found it hard to live together peacefully. Considering that during that span of time White Democrats in the South used the KKK to torment and kill Blacks, founded Planned Parenthood who, in the words of their founder Margret Sanger, “do not want word to go out that we want to exterminate the Negro population” (33), and passed the Jim Crow segregation laws that plagued the South for years; it seems that Lincoln’s predictions were actually semi-fulfilled.

Most importantly however, is not only that Lincoln believed that equality was impossible due to the opinions of the White race and the perceived physical differences between them and the Negros, he also feared that if such equality were to happen, it would bring about a “race war”; a guerilla style conflict resulting from the Whites in the North arming the Black soldiers whom they had trained, so that they may deal with the oppression dealt them by “their late masters.”

While we are thankful that Lincoln was wrong in this fear, it is certainly easy to understand why he would believe it could happen. The president had just witnessed a war that, while mainly resulted from the secession of certain states, had racial elements involved at its very core. To put it bluntly; the South seceded because they wanted to keep enslaving the Black race, and it was the Civil War that sought to put an end to this slavery/race-based secession. As President Lincoln once told a group of (free) Black ministers:

“See our present condition — the country engaged in war! — our white men cutting one another’s throats, none knowing how far it will extend; and then consider what we know to be the truth. But for your race among us there could not be war, although many men engaged on either side do not care for you one way or the other. Nevertheless, I repeat, without the institution of slavery, and the colored race as a basis, the war would not have an existence.” (31)

With the recognition of what Lincoln saw happening all around him, it is perfectly understandable why he believed that a race war could break out between Blacks and their former White masters if social and political equality was reached. Again, does this make him right? Absolutely not; but understanding what he had witnessed and where he was coming from shows that his beliefs were not based in a vile hatred of the Black race, but rather, on the experiences he had, the things he had witnessed, and the faulty predictions that came from those experiences.

It is also true that Lincoln, feeling equality was impossible and that the two races could not live together in peace, favored exporting the Negro race to places such as Liberia; and while it is easy to freak out about Lincoln wanting to send all the Black people back to Africa, this subject again must be viewed with clarity. It is very easy to assume what Lincoln’s plan was, especially considering the deportation of illegal aliens that we have witnessed in our time; but Lincoln’s plan was not one that endorsed “rounding them all up and shipping them off.”

The plan that Lincoln endorsed (which was very similar to one advocated by Jefferson) was A. to send African Americans to the Republic of Liberia, and other countries who’s governments were very similar in structure to the U.S.; and B. was not to be enacted without the consent of the Negroes in question, which is why Lincoln tried hard to drum up Black support for the plan (which ultimately failed). (34)(35)

Lincoln truly believed that the futures of both the White and Black races would be better if separated, which is why he advocated the plan he did; it was not, as some would claim, because he had evil intentions. But even those well-intentioned plans can be ultimately the wrong idea, and the wrong choice; we should be thankful that Lincoln’s plan failed, because it was a bad one, but we shouldn’t go as far as to paint Lincoln an evil man because of this issue.

The final criticism of Lincoln (and by far the weakest one), is based on his belief that the White race should be superior; and while it is true that our former President said: “while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race” and “I…am in favor of the race to which I belong having the superior position”; opponents point to Lincoln saying this as if this is such damning evidence that Lincoln was a horrible man; but I postulate that Lincoln was simply answering how any logical human being would.

To understand why he would say such things, we must remember what Lincoln believed; Abraham Lincoln believed that equality between the races was impossible, and given this belief, it logically follows that if equality is impossible, one race must be superior to the other. It is with that belief firmly in mind that Lincoln advocated for the White race, his race, to hold the position of superiority; and why wouldn’t he? It is the only logical thing for him to say! If one believes that one race must be superior to the other, then it is obvious that that person would want their race to be in the superior position; after all, no one wants their race to be inferior, subjugated, and in the subordinate position. I guarantee you that if you were to ask any White person or any Black person which race should be superior (in the context of Lincoln’s belief), both races would answer that their race should hold the superior position.

So does this make Lincoln evil? Of course not, it makes him logically consistent; of course as previously mentioned, the belief that equality was impossible has since been proven wrong, and thankfully so, but just because Lincoln was being logically consistent in his wrong belief, does not mean he was a bad man for it.

I think Lincoln’s friend, ex-slave Frederick Douglass described Lincoln very well on multiple occasions; for example, in his Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln (1876), Douglass stated:

“It must be admitted, truth compels me to admit, even here in the presence of the monument we have erected to his memory, Abraham Lincoln was not, in the fullest sense of the word, either our man or our model. In his interests, in his associations, in his habits of thought, and in his prejudices, he was a white man.

He was preeminently the white man’s President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men. He was ready and willing at any time during the first years of his administration to deny, postpone, and sacrifice the rights of humanity in the colored people to promote the welfare of the white people of this country. In all his education and feeling he was an American of the Americans. He came into the Presidential chair upon one principle alone, namely, opposition to the extension of slavery…The name of Abraham Lincoln was near and dear to our hearts in the darkest and most perilous hours of the Republic. We were no more ashamed of him when shrouded in clouds of darkness, of doubt, and defeat than when we saw him crowned with victory, honor, and glory. Our faith in him was often taxed and strained to the uttermost, but it never failed. When he tarried long in the mountain; when he strangely told us that we were the cause of the war; when he still more strangely told us that we were to leave the land in which we were born…

…Despite the mist and haze that surrounded him; despite the tumult, the hurry, and confusion of the hour, we were able to take a comprehensive view of Abraham Lincoln, and to make reasonable allowance for the circumstances of his position. We saw him, measured him, and estimated him; not by stray utterances to injudicious and tedious delegations, who often tried his patience; not by isolated facts torn from their connection; not by any partial and imperfect glimpses, caught at inopportune moments; but by a broad survey, in the light of the stern logic of great events… It mattered little to us what language he might employ on special occasions; it mattered little to us, when we fully knew him, whether he was swift or slow in his movements; it was enough for us that Abraham Lincoln was at the head of a great movement, and was in living and earnest sympathy with that movement, which, in the nature of things, must go on until slavery should be utterly and forever abolished in the United States.

When, therefore, it shall be asked what we have to do with the memory of Abraham Lincoln, or what Abraham Lincoln had to do with us, the answer is ready, full, and complete…under his wise and beneficent rule we saw ourselves gradually lifted from the depths of slavery to the heights of liberty and manhood; under his wise and beneficent rule, and by measures approved and vigorously pressed by him, we saw that the handwriting of ages, in the form of prejudice and proscription, was rapidly fading away from the face of our whole country… under his rule we saw the internal slave-trade, which so long disgraced the nation, abolished, and slavery abolished in the District of Columbia; under his rule we saw for the first time the law enforced against the foreign slave trade, and the first slave-trader hanged like any other pirate or murderer; under his rule, assisted by the greatest captain of our age, and his inspiration, we saw the Confederate States, based upon the idea that our race must be slaves, and slaves forever, battered to pieces and scattered to the four winds; under his rule, and in the fullness of time, we saw Abraham Lincoln, after giving the slave-holders three months’ grace in which to save their hateful slave system, penning the immortal paper, which, though special in its language, was general in its principles and effect, making slavery forever impossible in the United States. Though we waited long, we saw all this and more…

… I have said that President Lincoln was a white man, and shared the prejudices common to his countrymen towards the colored race. Looking back to his times and to the condition of his country, we are compelled to admit that this unfriendly feeling on his part may be safely set down as one element of his wonderful success in organizing the loyal American people for the tremendous conflict before them, and bringing them safely through that conflict. His great mission was to accomplish two things: first, to save his country from dismemberment and ruin; and, second, to free his country from the great crime of slavery…Though Mr. Lincoln shared the prejudices of his white fellow-countrymen against the Negro, it is hardly necessary to say that in his heart of hearts he loathed and hated slavery… Few great public men have ever been the victims of fiercer denunciation than Abraham Lincoln was during his administration. He was often wounded in the house of his friends. Reproaches came thick and fast upon him from within and from without, and from opposite quarters. He was assailed by Abolitionists; he was assailed by slave-holders; he was assailed by the men who were for peace at any price; he was assailed by those who were for a more vigorous prosecution of the war; he was assailed for not making the war an abolition war; and he was bitterly assailed for making the war an abolition war… for no man who knew Abraham Lincoln could hate him — but because of his fidelity to union and liberty, he is doubly dear to us, and his memory will be precious forever.

Fellow-citizens, I end, as I began, with congratulations. We have done a good work for our race today. In doing honor to the memory of our friend and liberator, we have been doing highest honors to ourselves and those who come after us…When now it shall be said that the colored man is soulless, that he has no appreciation of benefits or benefactors; when the foul reproach of ingratitude is hurled at us, and it is attempted to scourge us beyond the range of human brotherhood, we may calmly point to the monument we have this day erected to the memory of Abraham Lincoln.” (36)

And in an 1865 thank you letter to Lincoln’s wife (who had sent him the President’s favorite walking stick), Douglass told Mrs. Lincoln:

“Mrs. Abraham Lincoln:

Dear Madam: Allow me to thank you as I certainly do thank you most sincerely for your thoughtful kindness in making me the owner of a cane which was formerly the property and the favorite walking staff of your late lamented husband – the honored and venerated President of the United States. I assure you, that this inestimable memento of his presidency will be retained in my possession while I live – an object of sacred interest – a token not merely of the kind consideration in which I have reason to know that the President was pleased to hold me personally, but as an indication of his humane interest [in the] welfare of my whole race. With every proper sentiment of Respect and Esteem,

I am, Dear Madam, your obedient,

Frederick Douglass”

Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States; was he a perfect man? No; but despite his flaws, despite his faults, he was a good man and a good President. People who try to paint Lincoln as a vile racist, who did not care about slavery or the Black race are simply put, ignoring history, and are downright wrong. Lincoln has long been considered by most to be one of our greatest Presidents, and rightly so, which is why all attempts to discredit him must be addressed, and corrected. Of course there is another criticism of Lincoln in regards to his handling of the Constitution during the Civil War, but that my friends, is a topic for another day.

Thank you so much for reading the Bottom Line’s Civil War trilogy; I really hope you enjoyed this series of articles, and were able to learn something from them. If you enjoyed these pieces on the Civil War, please share them with your friends and family, and keep coming back for more historical pieces from the Bottom Line.

Sources:

1. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume II, “Speech at Peoria, Illinois” (October 16, 1854), p. 271.

2. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume II, “Speech at Peoria, Illinois” (October 16, 1854), p. 255.

3. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume II, “Speech at Peoria, Illinois” (October 16, 1854), p. 266.

4. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume II, “Speech at Springfield, Illinois” (October 4, 1854), p. 242.

5. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume II, “Fragment on Slavery” (April 1, 1854?), p. 222. http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/fragments-on-slavery/

6. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume II, “Letter to Joshua F. Speed” (August 24, 1855), p. 320.

7. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume III, “Letter To Henry L. Pierce and Others” (April 6, 1858), p. 376.

8. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume II, “Speech at Chicago, Illinois” (July 10, 1858), p. 492.

9. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume II, “Speech at Springfield, Illinois” (July 17, 1858), p. 514.

10. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume II, “Speech at Chicago, Illinois” (July 10, 1858), p. 501.

11. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume II, (August 1, 1858?), p. 532.

12. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume III, “Lincoln-Douglas Debate at Galesburg” (October 7, 1858), p. 226.

13. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume III, “Letter to James N. Brown” (October 18, 1858), p. 327.

14. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume III, “Lincoln-Douglas Debate at Quincy” (October 13, 1858), p. 276.

15. Lincoln’s ‘House-Divided’ Speech in Springfield, Illinois, June 16, 1858

16. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume III, “Speech at Cincinnati, Ohio” (September 17, 1859), p. 440.

17. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume III, “Speech at Chicago, Illinois” (March 1, 1859), p. 370.

18. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume III, “Speech at Cincinnati, Ohio” (September 17, 1859), p. 15.

19. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume III, “Letter To Henry L. Pierce and Others” (April 6, 1859), p. 376.

20. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume III, “Fragment on Free Labor” (September 17, 1859?), p. 462.

21. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume IV, “Speech at New Haven, Connecticut” (March 6, 1860), p. 16.

22. Lincoln’s Second Annual Message to Congress, December 1, 1862.

23. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume VII, “Letter to Albert G. Hodges” (April 4, 1864), p. 281.

24. Lincoln’s Fourth Annual Message to Congress, December 6, 1864.

25. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume VIII, “Speech to One Hundred Fortieth Indiana Regiment” (March 17, 1865), p. 361.

26. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume V, “Letter to Horace Greeley” (August 22, 1862), p. 388.

27. Roy P. Basler, editor, et al, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (New Brunswick, N. J.: Rutgers Univ. Press, 1953-1955 [eight volumes and index]), Vol. II, pp. 255-256. (Cited hereinafter as R. Basler, Collected Works.).; David A. Hollinger and Charles Capper, eds., The American Intellectual Tradition (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1989), vol. I, pp. 378-379.

28. John Hope Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of Negro Americans (New York: A. Knopf, 1964 [2nd ed.]), pp. 234-235. [In the fifth edition of 1980, see pages 108-109, 177.].; Leslie H. Fischel, Jr., and Benjamin Quarles, The Negro American: A Documentary History (New York: W. Morrow, 1967), pp. 75-78.; Arvarh E. Strickland, “Negro Colonization Movements to 1840,” Lincoln Herald (Harrogate, Tenn.: Lincoln Memorial Univ. Press), Vol. 61, No. 2 (Summer 1959), pp. 43-56.; Earnest S. Cox, Lincoln’s Negro Policy (Torrance, Calif.: Noontide Press, 1968), pp. 19-25.

29. R. Basler, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (1953), Vol. III, p. 16.; Paul M. Angle, ed., Created Equal?: The Complete Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858 (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1958), p. 117.

30. Lincoln/Douglas 4th Debate, Charleston, Illinois, Sept. 18th 1858: http://www.nps.gov/liho/historyculture/debate4.htm

31. R. Basler, et al, Collected Works (1953), vol. V, pp. 370-375.; A record of this meeting is also given in: Nathaniel Weyl and William Marina, American Statesmen on Slavery and the Negro (1971), pp. 217-221.; See also: Paul J. Scheips, “Lincoln … ,” The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 37, No. 4, pp. 428-430.

32. (Benjamin Butler, Autobiography and Personal Reminiscences of Major-General Benjamin F. Butler (Boston: 1892), pp. 903-908.; Quoted in: Charles H. Wesley, “Lincoln’s Plan for Colonizing the Emancipated Negroes,” The Journal of Negro History, Vol. IV, No. 1 (January 1919), p. 20.; Earnest S. Cox, Lincoln’s Negro Policy (Torrance, Calif.: 1968), pp. 62-64.; Paul J. Scheips, “Lincoln and the Chiriqui Colonization Project,” The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 37, No. 4 (October 1952), pp. 448-449. In the view of historian H. Belz, the essence of what Butler reports that Lincoln said to him here is “in accord with views … [he] expressed elsewhere concerning reconstruction.” See: Herman Belz, Reconstructing the Union: Theory and Policy During the Civil War (Ithaca: 1969), pp. 282-283. Cited in: N. Weyl and W. Marina, American Statesmen on Slavery and the Negro (1971), p. 233 (n. 44). The authenticity of Butler’s report has been called into question, notably in: Mark Neely, “Abraham Lincoln and Black Colonization: Benjamin Butler’s Spurious Testimony,” Civil War History, 25 (1979), pp. 77-83. See also: G. S. Borritt, “The Voyage to the Colony of Linconia,” Historian, No. 37 , 1975, pp. 629- 630.; Eugene H. Berwanger, “Lincoln’s Constitutional Dilemma: Emancipation and Black Suffrage,” Papers of the Abraham Lincoln Association (Springfield, Ill.), Vol. V, 1983, pp. 25-38.; Arthur Zilversmit, “Lincoln and the Problem of Race,” Papers of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Vol. II, 1980, pp. 22-45.)

33. Woman’s Body, Woman’s Right: A Social History of Birth Control in America, by Linda Gordon. http://www.dianedew.com/sanger.htm

34. Bedford Pim, The Gate of the Pacific (London: 1863), pp. 144-146.; Cited in: Paul J. Scheips, “Lincoln … ,” The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 37, No. 4 (1952), pp. 436-437.; James M. McPherson, The Negro’s Civil War (New York: 1965), p. 95.; “Colonization Scheme,” Detroit Free Press, August 15 (or 27), 1862.

35. Paul J. Scheips, “Lincoln … ,” The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 37, No. 4 (1952), pp. 437-438

36. Frederick Douglass: Selected Speeches and Writings, ed. Philip S. Foner (Chicago: Lawrence Hill, 1999), 616-624. http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/oration-in-memory-of-abraham-lincoln/

37. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/exhibits/douglass_exhibit/transcript.html

Ronald Reagan Quote of the Week

Good citizenship and defending democracy means living up to the ideals and values that make this country great. ~ Ronald Reagan

Founding Father Quote of the Day

Liberty is not to be enjoyed, indeed it cannot exist, without the habits of just subordination; it consists, not so much in removing all restraint from the orderly, as in imposing it on the violent. ~ Fisher Ames

Glenn Beck, Mark Levin, and Article V

A couple months ago, Glenn Back interviews radio personality, Constitutional Lawyer, and author Mark Levin about his new book The Liberty Amendments; a book that advocates using Article V of the Constitution to take back the power that Washington has wrongly grabbed over the last 100 years (a case that is very similar to the one being made by Constitutional Lawyer Michael Farris). Below is the half-an-hour interview, and it is well worth the listen.

Experts: Obamacare Website should only cost $5-10 Million

The failure continues; the Daily Caller reports:

On Wednesday night, Sean Hannity had two tech experts on his Fox News show to discuss the continuing problems of the Obamacare website. At the end of the interview, Hannity asked the experts how much it would have cost them to build a site similar to healthcare.gov that both operated properly from the beginning and was built secure to protect users’ sensitive information.

“I would say to build a site like this with the infrastructure, the architecture around it, you are looking at maybe $5 million to $10 million at a very maximum rate,” said David Kennedy, president of the technology firm TrustedSec. “It isn’t rocket science.”

The website should only cost between five and ten million dollars, and yet what is the actual cost? It is one billion dollars and counting; once again it is clear that a government who cannot even adequately run a website, will not be able to adequately provide healthcare. A government who can’t even spend what they were supposed to spend on a website, will not be able to keep Obamacare within the price range they promised. I’m telling you Republican candidates, you must hammer this issue! Mary Landrieu, a Democrat up for reelection, is saying she’d vote for this Obamacare disaster again! Hammer this hard! Obamacare is a losing issue, and the evidence is mounting for our side, I just hope we are smart enough to use it.

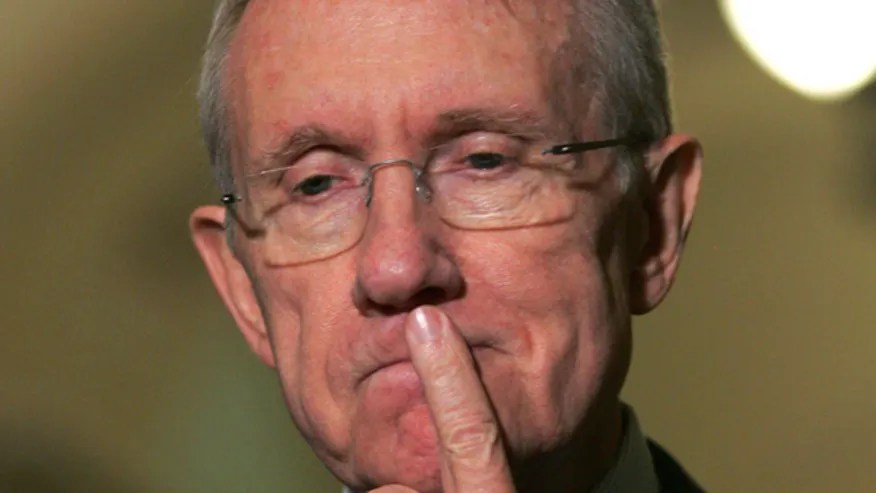

Harry Reid gives Obamacare Exemption to some Staffers

According to CNN:

In September, Reid told reporters, “Let’s stop these really juvenile political games — the one dealing with health care for senators and House members and our staff. We are going to be part of exchanges, that’s what the law says and we’ll be part of that.”

That’s true. Reid and his personal staff will buy insurance through the exchange.

But it’s also true that the law lets lawmakers decide if their committee and leadership staffers hold on to their federal employee insurance plans, an option Reid has exercised.

Reid spokesman Adam Jentleson emphasized, “We are just following the law.”

“We are just following the law”; yes, because that makes what you are doing less despicable. We need to understand what is going on here; Harry Reid thinks Obamacare is such a good program that everyone should be enrolled in it…except for some of his staffers. You know that Conservative argument that goes “if Obamacare is so great, why don’t the politicians take part in it?” That criticism belongs right here, as the same applies to the staffers of a politician. Harry Reid is wronging the American people by forcing them to suffer from Obamacare while giving exemptions to chosen staff members, and if any liberal or Democrat begs to differ with this assertion, they are just flat out wrong.

Ronald Reagan Quote of the Week

Freedom is indivisible – there is no “s” on the end of it. You can erode freedom, diminish it, but you cannot divide it and choose to keep “some freedoms” while giving up others. ~ Ronald Reagan